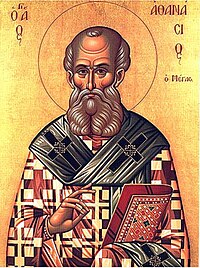

Today is the feast day of St. Athanasius, whose chops as an opponent of heresy are second to none; and for that reason, and because of some of the reading I've been doing for the conclusion of our Christology class, as well as some recent news stories in which the Church is unnecessarily type-cast as the antagonist, I have been pondering a bit this phenomenon of increasing open, vocal, assertive, brazen anti-Christian rhetoric and posturing. It certainly verges on discrimination, although it's not yet formally entrenched anywhere in the US, merely materially ascendant in certain places.

Today is the feast day of St. Athanasius, whose chops as an opponent of heresy are second to none; and for that reason, and because of some of the reading I've been doing for the conclusion of our Christology class, as well as some recent news stories in which the Church is unnecessarily type-cast as the antagonist, I have been pondering a bit this phenomenon of increasing open, vocal, assertive, brazen anti-Christian rhetoric and posturing. It certainly verges on discrimination, although it's not yet formally entrenched anywhere in the US, merely materially ascendant in certain places.Dominus Iesus (2000) hit the nail squarely on the head in listing, in a very general sort of way, the nature of the erroneous thinking involved here:

4. The Church's constant

missionary proclamation is endangered today by relativistic theories which seek

to justify religious pluralism, not only de

facto but also de iure (or in

principle). As a consequence, it is held that certain truths have been

superseded; for example, the definitive and complete character of the revelation

of Jesus Christ, the nature of Christian faith as compared with that of belief

in other religions, the inspired nature of the books of Sacred Scripture, the

personal unity between the Eternal Word and Jesus of Nazareth, the unity of the

economy of the Incarnate Word and the Holy Spirit, the unicity and salvific

universality of the mystery of Jesus Christ, the universal salvific mediation of

the Church, the inseparability "while recognizing the distinction" of the

kingdom of God, the kingdom of Christ, and the Church, and the subsistence of

the one Church of Christ in the Catholic Church.

The roots of these problems are to be found in certain presuppositions of

both a philosophical and theological nature, which hinder the understanding and

acceptance of the revealed truth. Some of these can be mentioned: the conviction

of the elusiveness and inexpressibility of divine truth, even by Christian

revelation; relativistic attitudes toward truth itself, according to which what

is true for some would not be true for others; the radical opposition posited

between the logical mentality of the West and the symbolic mentality of the

East; the subjectivism which, by regarding reason as the only source of

knowledge, becomes incapable of raising its "gaze to the heights, not daring

to rise to the truth of being"; the difficulty in understanding

and accepting the presence of definitive and eschatological events in history;

the metaphysical emptying of the historical incarnation of the Eternal Logos,

reduced to a mere appearing of God in history; the eclecticism of those who, in

theological research, uncritically absorb ideas from a variety of philosophical

and theological contexts without regard for consistency, systematic connection,

or compatibility with Christian truth; finally, the tendency to read and to

interpret Sacred Scripture outside the Tradition and Magisterium of the Church.

One part of the answer is, as always, merely power. The Church is pretty much the only coherent, readily articulated, and systematic point of view that stands against all of the "-isms" of the modern world, which are a threat to man or to the dignity of man. And those various "-isms" would love to be able to defeat the Church in some way, both to be seen as more powerful, and to remove a strong opponent to their untrammelled domination.

But I think we shouldn't underestimate the consequences of muddled thought in and of itself. Moral relativism is taught daily in our public schools, sometimes overtly, often by default; subjectivism is everywhere, with its stupid but powerful idea that truth is best recognized by an observable emotional response; the problem of "metaphysical emptying" is everywhere, quite apart from its Christological and ecclesiological implications, teaching people to accept lower order goods and to accept division in place of unity; eclecticism makes rational argumentation much harder than it needs to be; and so forth. The net effect of all of these incomplete or inadequate ways of thinking is that most people are more or less convinced that what's good for them (often in a reductive and/or immediate sense) is the same as the common good; and therefore if others disagree with them, these others must be opposed to them, in the manner of trying to deny them some good.

St. Athanasius, for all his trials and struggles for the apostolic faith of the Church, didn't have this problem to deal with. His opponents were, by and large, at least rational. Arius thought he was solving the difficult problem of divine impassibility in the Incarnation. Constantius thought he was doing what was good and necessary for the unity of the Empire. That they were mistaken about these things didn't mean they couldn't be reasoned with, and indeed, eventually, the process of rational argument did secure the apostolic teaching and the rejection of Arianism fairly definitively.

In our evangelization today, at the individual level, I think we still need to do this. How we talk about the faith, about our worldly and spiritual experiences, our consistency of word and action, and so on, constitute a kind of argument about most basic principles which is readily apparent to those around us. And since people are not usually attracted by philosophy (a systematic presentation of the truth as ideas) but by holiness (a very different but no less systematic presentation of the truth in action), this is the right way to proceed.

For those who think we are opposed to them personally merely because we disagree with them about ideas, it is the witness of consistent and joyful imitation of Christ by those who are known to them which has a chance to convince of our goodwill, even if conversion never follows.

But at the wider level, this kind of personal approach doesn't work. Here the clash of ideas and perceptions happens in a separate way from our personal witness. Consistency and joy still matter here, but somehow it needs to be translated to that more impersonal level. Here, martyrial witness is a powerful kind of argument. Those who are willing to suffer for Christ (in whatever sense; in other words, to carry the Cross in daily life, without complaint, even when it is unjust) are appealing in this sense. But the appeal rests on the coherence of the tradition or identity - in this case, the apostolic Tradition and the identity of bearing Christ's name as Christians. If that tradition and identity is not generally perceived as internally coherent - in other words, if Christians are generally perceived to be disloyal to their own tradition, for whatever reason - at one level, it doesn't even matter if it's true or not - then the quality of the witness is badly undermined.

So as St. Athanasius knew so well, a well-formed Church is really necessary for the project of evangelization. The weakness of our evangelization in the West in the past three-four generations is a symptom of insufficient internal coherence, consistency, joy, and zeal in bearing the Name and the Cross of our Redeemer. John Paul II wrote the same:

Difficulties both internal and external have weakened the Church's missionary thrust toward non-Christians, a fact which must arouse concern among all who believe in Christ. For in the Church's history, missionary drive has always been a sign of vitality, just as its lessening is a sign of a crisis of faith. (Redemptoris Missio, 2)

The Catechism of the Catholic Church is a major step in the right direction. So is a coherent anthropology at the root of our formation programs (four pillars of human, spiritual, intellectual, and pastoral formation). So is the plethora of solid and orthodox Bible studies which use well all the tools available to us, without abusing the historical critical method in the manner which leads to supplanting Christian identity with some mere political ideology. So is the new Missal's use of a consciously sacral language for worship. So is Friday abstinence and the daily Rosary, as universally shared elements of a clear, Catholic identity. And so on... these are the things, when used well and often, that build up our conviction, our faith, our zeal, and therefore our ability to evangelize the increasingly unfamiliar world around us.

No comments:

Post a Comment